Backwards Walking & Rehabilitation

- by Joanna Blair

- •

- 01 Apr, 2018

- •

Besides it possibly making one feel rather silly or odd to start practising backward walking (BW) within a gym, sports complex or out in an open public park, it has been a topic of interest since the 1980s. The skill is also used as part of a rehabilitation tool by various manual therapists who aim to improve strength and balance along with reducing various lower-extremity injuries and as an injury prevention strategy (4, 5, 12).

BW & Improved Ankle Joint Kinematics

A study conducted by Kim et al., (2011) discovered that the ankle joint used the largest amount of joint power during the mid stance phase (by 10-30%) which implies that the greatest momentum during backwards walking could be generated at the ankle joint. When comparing BW to forwards walking (FW), joint power in the hip and knee joints were generated the most during the pre-swing phase during FW (9).

The study by Dufek et al., (2014) compared the balance and lower extremity kinematic patterns between healthy younger and healthy older adults following a four week intervention of BW with results showing a significantly improved balance and stability amongst participants. With toe clearance during the swing phase of the gait cycle reducing with age, backward walking in this study found that older adults exhibited a significantly greater range of movement at the ankle vs young adults (4).

BW & Rehabilitation of the Knee & Patellofemoral Joint

Patellofemoral pain (PFP) accounts for approximately 25% of knee injuries in athletes (6).Flynn and Soutas-Little (2012) analysed that backwards running (BR) could reduce patellofemoral joint compression forces (PFJCF), which otherwise aggravates symptoms, is significantly lowered than in forwards running (FR). Thus, implying that BR can be used as part of rehabilitation for patients with PFP. BR as a form of exercise needs to be performed with caution as a case study showed that if implemented incorrectly it can lead to overuse injury (15).

Dr Mercola (2012) highlights the need to take particular caution whilst BR to avoid trips or falls, a clear, flat path would be wise to prevent running into objects/ people and keep the head facing forwards (and not over the shoulder) to avoid other structural problems.

BW up an incline may be an effective tool to assist an individual to obtain greater knee flexion during gait (11). Cipriani and Armstrong (1995) discovered that during initial contact during backward walking the knee was flexed at approximately 31° at 0% incline grade and flexed at approximately 42° at a 10% incline grade.

With the goal of improving knee joint range of motion, in many knee joint rehabilitation programs for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, fracture management, and joint replacement, backwards walking could be considered as a good form of exercise within a rehabilitation programme.

BW & Lower Back Pain

A small study by Dufek et al., (2011) concluded reduced lower back pain (LBP), improved lower back range of movement and flexibility after individuals with the condition followed a 3 week programme of BW exercise.

Hip extension and knee flexion are greater during BW (6.). The increase in hip extension and concomitant lumbar spine extension put increased loading on the facet joints and open up the disc spaces causing a reduction in compressive loading to the intervertebral discs (6).

BW and Cardiovascular and Metabolic Benefits

The American College of Sports Medicine guidelines report that exercise needs to be maintained at an intensity of 50% to 85% maximum oxygen consumption (VO2max) or 60% to 90% maximum heart rate (HRmax) to improve cardiovascular fitness (12).

Hooper et al., (2004) studied the cardiovascular effects of FW versus BW on HR and VO2 at treadmill grades at 5%, 7.5%, and 10% at a speed of 67.0 m/min (2.5 mph). The study concluded that heart rate (HR) and oxygen consumption (VO2) have been shown to be higher during BW than FW at a 0% treadmill grade and similar relationships have been reported for treadmill grades of 1% and 5%.

The metabolic cost of backward running was also higher than during BW. Minute ventilation (VE), VO2, and HR were 88%, 31% and 15% higher, respectively, during backward running than during forward running (12). Cavagna et al., (2011) concluded that backwards running requires approximately 30 percent more metabolic energy expenditure than forward running, meaning we burn more calories!

The results of a study by Terblanche et al., (2004) found that backward locomotion can improve cardiorespiratory fitness after a six-week backward walking programme and a reductioin in body fat and change in body composition.

BW and Sensorimotor Activation

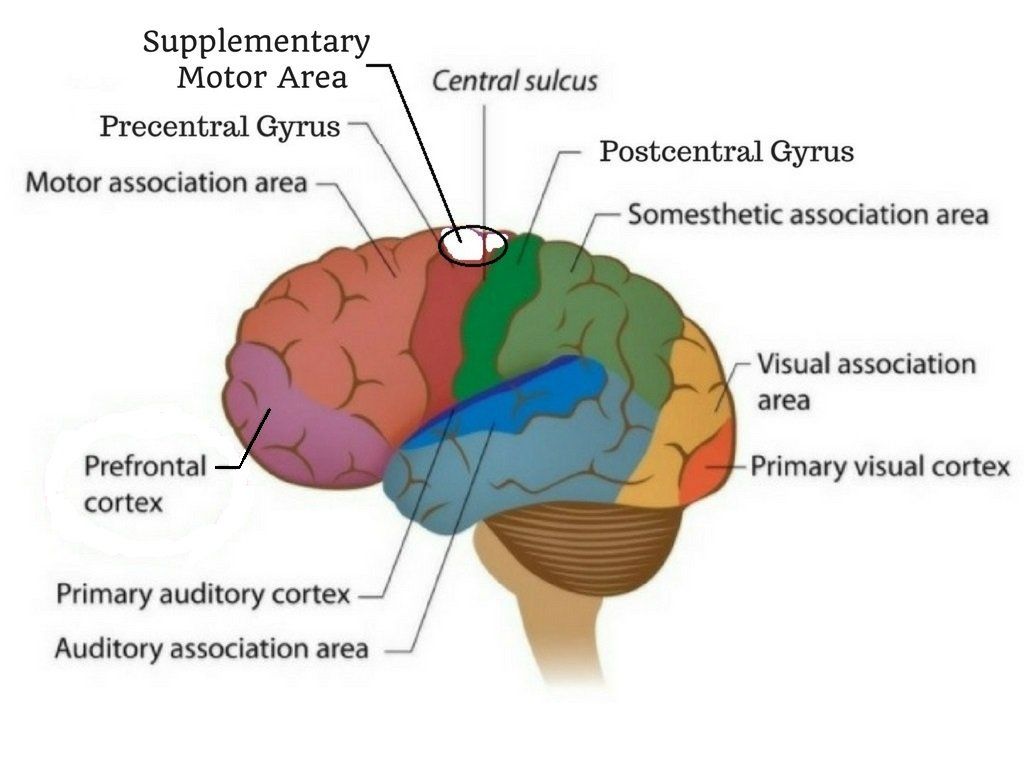

Kurz et al., (2012) results showed that oxygenated hemoglobin (oxHb) was greater in certain areas of the brain; the supplementary motor area (SMA), pre-central gyrus, and superior parietal lobule when participants walked backwards rather than forwards. The study found that backwards walking presents more of a challenge to the nervous system as it controls gait and stepping pattern. There was also the discovery of there being a significant decrease in the amount of deoxygenated hemoglobin (deHb) in the SMA whilst walking backwards.

BW and Children with Hemiplegic Cerebral Palsy

Kim et al., (2017) studied a small number of children with spastic hemiplegic cerebral palsy and how backward walking might help. Muscle growth is slower than bone growth in spastic cerebral palsy which affects joint construction as they grow. Children with this condition have reduced balance whilst standing, poor motor coordination whilst walking which results in a short stride, increased stride frequency and poor stability (8). Consequently, children with cerebral palsy consume more energy during any form of activity.

Kim et al.,

(2017)concluded that backward walking can significantly increase the single leg standing time on the affected, weaker side, improve the children's balance, symmetry and stair climbing.

Further study is required with the low number of participants, the lack of follow-up and assessment of muscle strength and energy expenditure when evaluating the effects of backward walking training in children with spastic hemiplegic cerebral palsy.

Conclusion:

Backwards walking has been seen to:

- Increase heart rate.

- Improve cardiorespiratory fitness.

- Improve balance.

- Improve body composition.

- Help lower back pain, joint flexibility and improve range of movement.

- Help with the rehabilitation for patello-femoral joint knee pain.

- Improve coordination.

- Improve lower extremity active range of movement and strength.

- Improve toe clearance during gait cycle.

- Increase metabolism for BR (burning more calories).

- Reduce the ocurrence of falls.

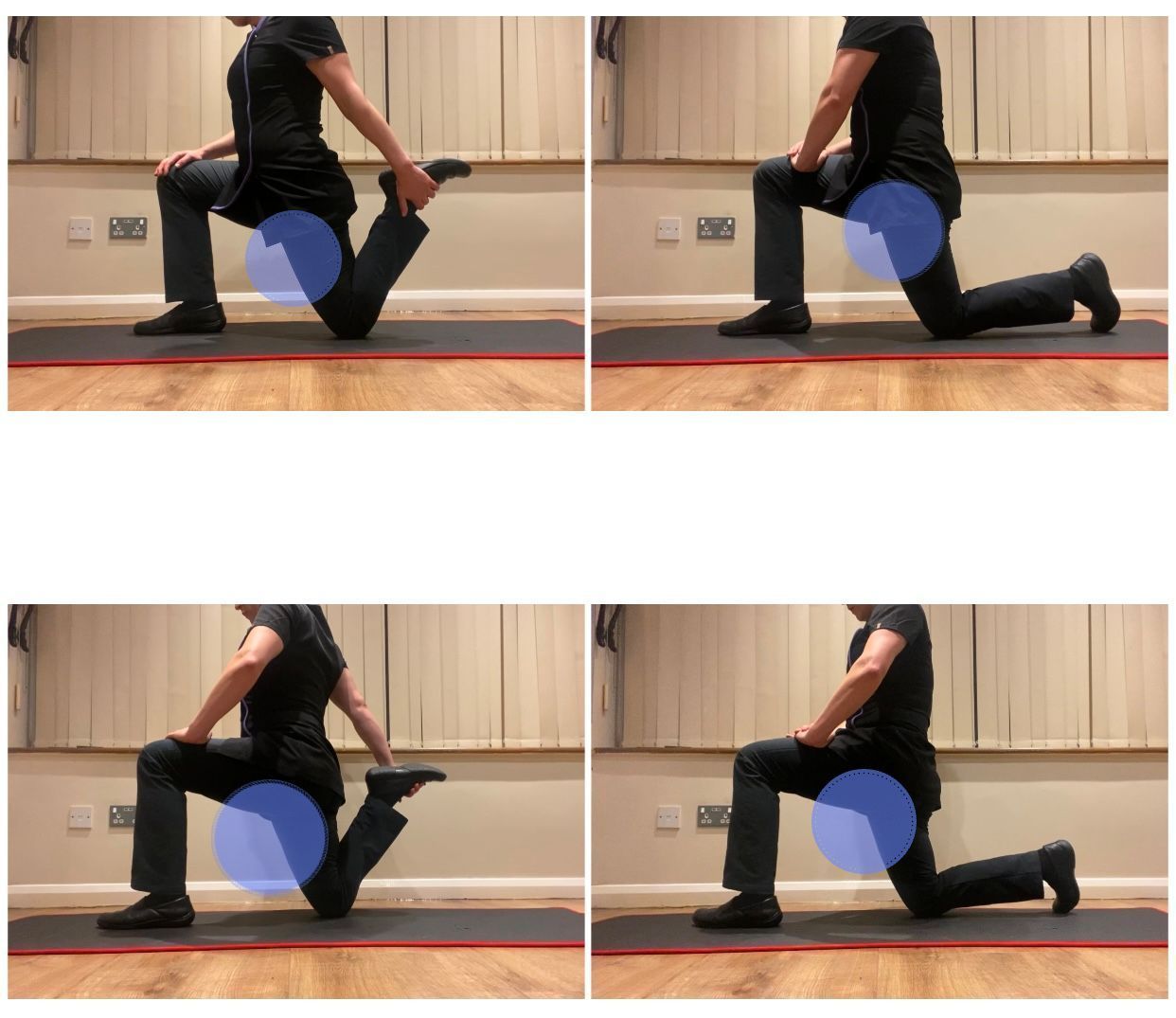

It must be noted, that there is a certain technique to BW which is important to prevent further injury for if performed incorrectly. The skill requires both feet to remain pointing straight/ forwards (at a 12 o'clock direction) with a good toe clearance by lifting the feet clearly off the floor, arm swing is important to maintain balance. Walking along a line like the video below might help to encourage straighter foot positioning and body awareness. You may note how the right foot has the tendency to laterally rotate during the toe-heel contact phase causing malalignment in the right knee, hip and pelvis and other compensatory movement patterns, can you see them?

References

1. Adesola, A. M. and Azeez, O. M. (2009) Comparison of Cardio-Pulmonary Responses to Forward and Backward Walking and RunningAfr. J. Biomed. Res. Vol. 12, No. 2

2. Cavagna, G. A., Legramandi, M. A., La Torre, A. (2011) Running backwards: soft landing-hard takeoff, a less efficient rebound. Proc Biol Sci, 7;278(1704):339-46.

3. Cipriani DJ, Armstrong CW, Gaul S. (1995) Backward walking at three levels of treadmill inclination: an electromyographic and kinematic analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther; 22: 95-102.

4. Dufek, J., Mercer, J., et al. (2014) Effects of Backward Walking on Balance and Lower Extremity Walking Kinematics in Healthy Young and Older Adults, Department of Kinesiology and Nutrition Sciences, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Las Vegas.

5. Dufek, J.S. (2002) Exercise variability: a prescription for overuse injury prevention. Health Fit Journal; 6:18-23.

6. Dufek, J., House, A., Mangu, B., Melcher, G., Mercer, J. (2011) Backward Walking: A Possible Active Exercise for Low Back Pain Reduction and Enhanced Function in Athletes, 14; 2: 17-26.

7. Flynn, T. W., Soutas-Little, R. W. (1995) Patellofemoral Joint Compressive Forces in Forward and Backward Running, Journal and Sports Physical Therapy, 21 (5): 277-82.

8. Hooper, T. L., Dunn, D. M., Props, E. J., Bruce, B. A., Sawyer, S. F., John A. D. (2004) The Effects of Graded Forward and Backward Walking on Heart Rate and Oxygen Consumption, J Orthop Sports Phys Ther: 34; 2: pp. 65-71.

9. Kim, Y. K., Jang, H-I., Ko, K-H., Chang, W-N., Lim, S-K. (2017)Effect of Backward Walking Training on Dynamic Balance in Children with Spastic Hemiplegic Cerebral Palsy,5Department of Physical Therapy, Severance Rehabilitation Hospital, Yonsei University Health System,

10. Kim, Y., Son, J., kim, J., Hwang, S. (2011) Gait Mechanism of the Backward Walking, Department of Biomedical Engineering and Institute of Medical Engineering, Yonsei University.

11. Kurz, M. J., Wilson, T. W., Arpin, D. J. (2012) Stride-time variability and sensorimotor cortical activation during walking,

2011 Elsevier, NeuroImage 59 (2012) 1602–1607.

12. Hooper, T. L., Dunn, D. M., Props, E. J., Bruce, B. A., Sawyer, S. F., John A. D. (2004) The Effects of Graded Forward and Backward Walking on Heart Rate and Oxygen Consumption, J Orthop Sports Phys Ther: 34; 2: pp. 65-71.

13. Mercola, (2012) Stimulate Your Fitness IQ By Walking Backward, https://fitness.mercola.com/sites/fitness/archive/2012/12/14/walking-backward.aspx, Last visited 05/04/2018.

14. Roos, P. E., Barton, N. and van Deursen, R. W.M. (2012) Patellofemoral joint compressive forces in forward and backward running. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. J Biomech. 1; 45 (9): pp. 1656–1660.

15. Satterfield M., Yasumura K., Abrue S. (1993)Retro runner with ischial tuberosity enthesopathy. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. ;17(4):191–194. [PubMed].

16. Terblanche, E., Page, C., Kroff, J., Venter, R.E. (2004) The Effect of Backward Locomotion Training on the Body Composition and Cardiorespiratory Fitness of Young Women, Int. J. Sports Med; 25: 1 -6.